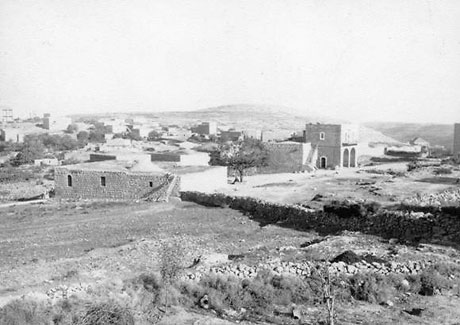

Images Above: Rula Halawani ‘Al-Bira’ (Old and New Diptych) Archival Artistic Inkjet Prints on Hahnemuhle Paper, 30 h. x 90 w. cm (ea), Edition of 5 (2009)

Courtesy of Selma Feriani Gallery

An Interview with Rula Halawani

March 2010

Alireza: How did you embark on your career as an artist?

Halawani: I believe that photography is art. Therefore, the day I decided to become a photographer is the day I became an artist. That day happened by complete chance. I was studying maths and physics at university in Canada. The first intifada was underway in Palestine, so for fear of not being able to return, I spent the summer in Canada rather than go home. In order to pass the time, I decided to take a summer course in photography, due to a lack of anything else to do. Within the first half an hour of that class, my mind was completely made up - I wanted to become a photographer. My father had refused to pay my way if I changed fields, but I was lucky enough to have received a full scholarship in photography. I felt like it was a sign that I was making the right decision, as if it were always meant to be.

A.A.: Why did you switch from photojournalism to art photography, and what marked the transition between the two?

R.H.: As a photojournalist, I was an outsider, a professional trying to remain detached. But remaining emotionless was too hard. So I figured that if I did things my way, the way I wanted, it would get easier. But, I was wrong, opening up the floodgates of emotion definitely does not make things easier. There was however, one very definite turning point, and that was when a child, a boy I knew, was shot dead in front of me, with a stone in his hand. That was the day I quit my job in photojournalism.

A.A.: What is the major difference between your photojournalistic work and your art photography?

R.H.: Well, previously, I was a news photojournalist and in a way I still am a photojournalist, though, not for the news. I consider myself a documentary photographer, which I believe still falls into the category of photojournalism. I do not consciously create art, I document and record in my own way, but art is what the end result seems to be, or so I’ve been told. I suppose that ‘my way’ involves finding a new approach to the complex subjects that I had always been photographing, a way that prompts my work to interact more with its audience. Even though I witnessed the subjects as a photojournalist, I tried to approach them in a way that introduced more nuance and ambiguity, which is what transforms it from mere photojournalism to visual art.

A.A.: What are you trying to accomplish or convey?

R.H. I’m not the best of long-term planners. My ideas come, and I carry them out. I suppose that my work is egocentric – it’s all about me - a self-portrait if you will. It is a reflection of my life and my experiences, which I wish to share. It just so happens that my people and my land are so much a part of me that they are what come across most strongly in my work.

A.A.: So is the political statement deliberate or a by-product?

R.H.: There is always a deliberate political statement to my work. There is no denying it, it’s so obvious!

A.A.: Is there any significance to portraying the images in diptychs other than to illustrate before and after?

R.H.: I chose the form of diptychs because it enhances my political statement - they effectively illustrate that we [Palestinians] were there, and still are, that our ‘presence’ has endured. Hence ‘Presence and Impressions’. Its proof for the world! Plus I found that it added a certain conceptual engagement to the archival significance of the work.

A.A.: Is there any further conceptual value that is not obvious to the observer?

R.H.: Well, I try to make sure that the title of the series is enough of a clue as to the conceptual content and hope that the audience can make that connection. I mean, ‘Presence and Impressions’ I believe is self-explanatory – We were once present and have left such an impression upon the place that it is as if we still are present. What the audience probably would not know is that ‘impressions’ also expresses that my photo is my personal impression of the same location in the archival photo. For as much as I tried to calculate the exact angle that the original picture was taken, the land had changed so much since, that the task was impossible.

A.A.: Is there any relevance to the lack of figural representation in your photographs?

R.H.: The obvious relevance would be to convey the absence of inhabitants after being depopulated. But more importantly, I really wanted to focus on the land and its significance, for even though the people are absent from the land, their presence is still felt because the land and the people are one and the same - inseparable. It took me a while after being away for so long to truly understand that. Furthermore, most photography on the subject of Palestine has tended to be so graphic and over-politicised and consequently, intractable. I find that the lack of figural representation to some extent, de-emotionalises a highly political subject, so that it becomes more approachable and discussion-friendly. After all, I want to promote dialogue, not stunt it.

A.A.: What are the challenges and difficulties you face? With your work in general and this series in particular.

R.H.: Oh god, the difficulties are endless, but that suits me fine. I don’t like to do things the easy way and I always embrace a challenge. Having been a photojournalist, I’ve retained all my contacts, which definitely come in handy. You need special permission for just about anything, and even then, despite the fact that you have permission, there’s no guarantee that the person lower down the bureaucratic ladder will be feeling accommodating.

As for this particular series, I had wanted to do something on depopulated villages for a long time, but couldn’t afford it. Finally with the Afaq grant, I could get started. Even then, finding the villages was near impossible as there is almost no record left of some of them whatsoever, no maps or directions or anything. Most of the time we followed our leads based on hearsay. Finding the old photographs was also a struggle and to restore them, even more so, for some of them are in very bad condition. But like I said, I love a challenge, and the end result makes it all worth it.

A.A.: How did you feel when you were carrying out this work? Did you experience any specific emotions at any particular time?

R.H.: There was in fact one particular event that impacted me most during the making of this series. During my research on the depopulated villages, I came across the name of a village called Kawkab al-Hawa, which literally translates to ‘planet of the wind’. I loved the name and wondered how and why it had come to be called that. However, as I have mentioned previously, there were no clues whatsoever as to where to find this village, so I quickly gave up on it. Whilst searching for another village called al-Bira, we asked a local for directions and they mentioned hearing of a village up on a mountain nearby which could be the one we were looking for. When we arrived at the peak, we were blasted by gusts of full-force winds that we could hardly open the car doors. We asked an old man who was sitting nearby what the name of the village was, and he replied ‘Kawkab al-Hawa’- Planet of the Wind. It was one of those surreal, magical and touching moments that gives you goose-bumps that I will never forget.

A.A.: Could you give us an idea of any future projects you are planning?

R.H.: I am indeed thinking of starting a new project, but it’s still too early to talk. I can however say that it will be an extension of this series as well as my other series, Lifta. I like to maintain a certain homogeneity and discourse between my works. It is important to me that they connect.