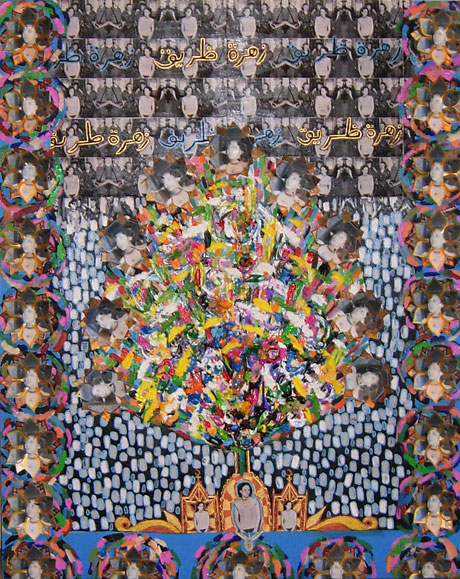

Mujahidat #1 24x30 2008

Mujahidat #2 36x48 2008

Mujahidat #3 24x30 2009

Mujahidat #5 24x30 2009

Mujahidat #7 24x24 2009

Mujahidat #8 36x48 2009

‘Battle of Algiers’ and the Artwork of Asad Faulwell

March 2010

Yasmine Mohseni writes on the series ‘Battle of Algiers’ by Iranian artist Asad Faulwell.

It all started with the Battle of Algiers. In 1966, Italian film director Gillo Pontecorvo directed a film depicting the violent events of the Battle of Algiers, an episode of the Algerian War of Independence that transpired between November 1954 and December 1960. In the film, paralleling reality, the National Liberation Front (FLN) comes head to head with French troops to liberate Algeria from French colonialism. During 2008 in Los Angeles, Asad Faulwell, a young Iranian-American art student completing his MFA at Claremont Graduate University, watched the film and found the involvement of female combatants fascinating. The scenes of women committing violent acts and fighting alongside their brothers-in-arms for Algerian independence lingered in Faulwell’s mind as he entered his studio. Through the exploration of this subject matter, he created a new body of work focusing on a richly complex topic. They allow him to elaborate on what is at the heart of his work: the process of creating a religious icon based on a secular figure.

Through books, articles and internet-based research, Faulwell has virtually become an expert on the subject of female FLN combatants. Since beginning the series in October 2008, he has already created eight mixed media works, and continues to be inspired by their stories. Yet before he turned his attention to this series, more prominent historical figures occupied his thoughts. In 2007, while still in graduate school, Faulwell began to work with images of modern Middle Eastern politicians. He found old photographs of Gamal Abdel Nasser, Mohammed Mossadegh and Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, which he applied to canvas, framing them with elaborate decorative paintings. His richly textured paintings simultaneously refer to Muslim prayer rugs and Christian altarpieces. All the while, the viewer is left wondering whether the artist considers his subjects iconic or if there is an underlying critical subtext. The answer, however, is a bit of both. “I leave it up to the viewer to decide. There are some people in the paintings who I really dislike and others who I like a lot, but I always display them in the same way.” A painting with the Ayatollah Khomeini is treated in the same style as one with Mossadegh. The question is not whether Faulwell prefers one to the other. Rather, he is asking by what criteria is one deemed holy or iconic. This is a difficult question to pose when the subjects are well-known politicians whose mere images can illicit strong reactions and who have a multitude of associations for a viewer. Yet, the question is no less complicated when the topic at hand is women fighters who fought for their country.

During the Algerian War of Independence, there were over 10,000 fighting women. In the city of Algiers, they fulfilled different types of missions for the FLN. Some were bombers and others provided aid to the men, such as hiding murder weapons or providing a safe house from French soldiers. Some women would alter their appearance to look French, making it easier to cross checkpoints between the predominately Arab Casbah neighborhood and the French parts of town. One particularly powerful moment in Pontecorvo’s film depicts a bleached blonde Arab woman flirting with French soldiers to get by a check point, while carrying a bomb in her purse destined for a cafe populated by young French revelers. For Faulwell, the film was a point of departure. He researched the individual women fighters, many who gained notoriety in Algeria and France. He supplemented his knowledge with sources like A Savage War of Peace by Sir Alistair Horne and Natalya Vince’s “Colonial and Post-Colonial Identities: Women Veterans of the ‘Battle of Algiers’”. As he delved into the subject, Faulwell began to appreciate its complexity. He learned that these women were used and abused by both sides: they fought for Algeria and they were captured, raped and tortured by the French. After the war, Algeria turned their back on many of these women, viewing them as, “…a poisonous legacy [of] French Colonialism, [many Algerians] associated secular law and women’s rights with the taint of colonial imposition…” writes Vince. Faulwell draws a parallel between the French sending Algerian men to the front lines during World War II and Algerian men sending their women to fight. “They [Algerian men] were taking women who they had no intention of empowering after the war, getting them to fight on the front lines and then turning their back on them as soon as the war was over.” The subject of female Algerian FLN fighters is intricate and merits serious consideration. And, as a source of inspiration for Faulwell, it resulted in a series of strong pieces that build on his earlier series of Middle Eastern political figures.

The first three paintings in the series represent the fighters Zhora Drif, Djamila Bouhired and Hassiba Ben Bouali. This was not a critical or conceptual choice, as the artist simply found these photos first. As he learned about other fighters and their stories, he would incorporate their photos. After completing the first three canvases, Faulwell began combining photos of fighters within the same composition. One technique that he favors is applying the same few pictures repeatedly. This repetition, like that of a mantra or prayer, achieves a sense of being in the presence of the spiritual or iconic. It also imbues his work with a visual cadence. This underscores his desire to investigate how people come to be considered holy. “What’s the process? Aesthetics is such a big part of that. I work with displaying people in a very grand way. But I do it with people who were not prophets.” This is especially effective when dealing with anonymous subjects such as female FLN fighters versus internationally recognized figures like Nasser or Khomeini. And it also raises the question of how people view and respond to images of female freedom fighters.

Although the artist would like his viewer to decide whether or not the subjects are worthy of being deemed holy, he is vocal in wanting to portray the female fighters in a positive light. “They were people who committed really violent acts, yes, but violent acts that I think were commendable and justifiable, if there’s such a thing.” Faulwell has noticed that people respond to this series in a very different way than to his previous one. Whereas some people have expressed hostility upon seeing photos of Nasser in Faulwell’s paintings, viewers are sympathetic towards the female FLN fighters. “With them [the female Algerian fighters] there’s always this notion that they’re victims. People are shocked that every single one of these women killed.” It is this dichotomy of viewing the Arab woman as a victim that makes the subject matter so compelling. These women planted bombs and fired guns, yet, even today people see them as victims. Faulwell, who has been tempted to get in touch with some of the living veterans, is particularly sympathetic towards Hassiba Ben Bouali, a prominent fighter and one of the few who died in battle. Faulwell possesses a sensitivity for the subject matter, which translates in his compositions.

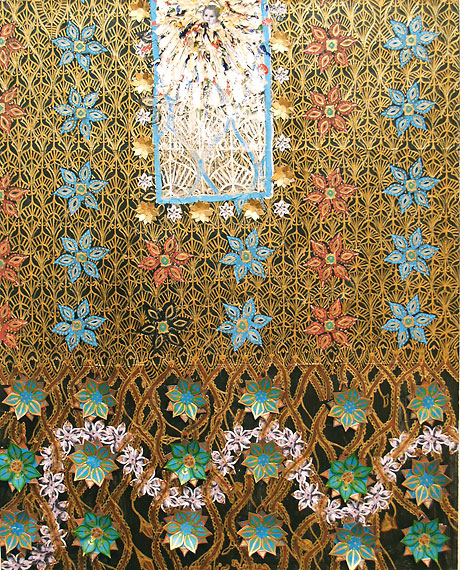

Over the past two years, Faulwell improved his technique to an extent that he is able to convey his concept in an increasingly effective way. The ‘Series’ 8’ canvases were completed in merely one year, yet in this short time span, Faulwell developed as an artist. In the painting of Zhora Drif, the earliest in the series, the photos are not well integrated in the loose composition and the chaotic brash centre is distracting. Yet, the triptych of Drif towards the bottom of the canvas, which takes a cue from Byzantine art, creates a balance in the work and foreshadows Faulwell’s potential. His most recent canvas, representing Djamila Bouazza, Djamila Bouhired, Zhora Drif, Daniele Minne, and Hassiba Ben Bouali, is very strong. The composition of the piece is conceived as a prayer rug with rich colors and bold symmetrical geometric patterns. His mastery of Islamic decorative arts is evident in this 2009 work, which weaves centuries-old motifs with photos of the twentieth-century female fighters, forming a harmonious composition. Faulwell has become comfortable with both his subject matter and his technique. That is another key to Faulwell’s work, aside from creating religious icons from secular figures, which to a certain degree can be essentially deemed as broaching the subject of modern Middle Eastern history.

As an undergraduate from the University of California at Santa Barbara, Faulwell briefly changed his major from art to Middle Eastern studies. For several years, he learned as much as he could on the region and the twentieth-century events that have defined the Middle East. When asked if his work is a study of his own identity, he is hesitant to follow that route. This is understandable given that so many artists from the Middle East today address issues of identity, often resulting in contrived work. As a man of both American and Iranian descent who has not traveled to the Middle East, he explains that portraying figures from the region’s modern history is a way to connect to his heritage. “I don’t have any real tangible every day connections. In that sense, I think my motivation of getting into the subject matter in the first place was identity-based, but in an indirect way.” The region remains fairly abstract for Faulwell, who was born and raised in the United States. He steers clear from the trite in his work by addressing the religious and secular through paintings and photos of the region’s renowned and anonymous. Issues of identity are a personal subtext and do not overpower his work. As a young man living in the U.S., Faulwell is ambitious to create a series based on Algerian female fighters, which has clearly been executed effectively. Not only have people reacted well when seeing this series, it has nearly sold out. While commerce is not the inevitable result, in this case, it does raise the question of whether the plight of these women has transcended borders, cultures and time. Perhaps that is their last legacy.