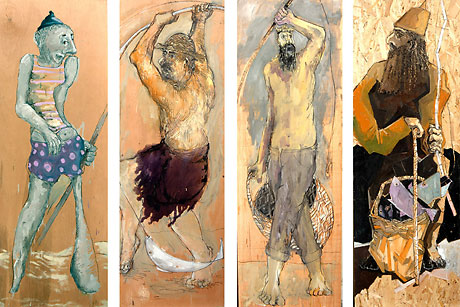

Bachannale

Strangulation

Fisherman

Marwan Sahmarani

The 2009-2010 Abraaj Capital Art Prize

October 2009

Asmaa Al-Shabibi writes on the Abraaj Capital Art Prize, and also interviews Abraaj Capital Art Prize winner Marwan Sahmarani.

The Abraaj Capital Art Prize was launched in 2008 as an initiative between Art Dubai and Art Dubai’s principal sponsor Abraaj Capital to promote artistic talent in the MENASA (Middle East, North Africa and South Asia) regions of the world. In its inaugural year, artists Nazgol Ansarinia, Zoulikha Bouabdellah and Kutlug Ataman (from Iran, Algeria and Turkey respectively) were each awarded US$200,000 to create the ‘project of their dreams’. Working closely with their chosen curators, these artists produced installation works which were unveiled at Art Dubai in 2009, and are now displayed at the Museum of Art and Design, New York, with further plans to travel to other prestigious institutions. This provided tremendous exposure for those artists whose talents are deserving of such international recognition. Yet on a more critical note, the prize is perhaps the finest example of a Middle East based corporate giant supporting and patronising the arts through utilizing such a direct and public approach. At one million dollars, the Abraaj Capital Art Prize yields itself as the most premium art prize in the world, which is certainly much needed at a time where public and private funding for art projects is lacking in the Middle East.

As of September, the three new winners of the Abraaj Capital Art Prize were announced and I caught up with one of its recipients, Marwan Sahmarani, who exclaimed that wining the prize was like ‘winning the marathon before the run had begun’. I had met Marwan about a year ago in Beirut, spending a few hours in his studio amongst his large-scale intense and dramatic works, and I was thrilled that he received the award. Born in 1970, he left his birth city Beirut in 1989 by moving to Paris to study at l’Ecole Supérieur d’Art Graphique. He has lived in Montreal since then, but recently moved back to Beirut.

Asmaa Al-Shabibi: Having attended Art Dubai last year, did seeing the prize at the fair motivate and inspire you to apply this year?

Marwan Sahmarani: I did see the works at the fair, but to be honest, I felt disconnected; it wasn’t until I received the details of the prize for 2010 that I made the connection between the installations at the fair and the Abraaj Capital Art Prize. At the time, I was in Canada contemplating my move back to Lebanon, and I was applying for many projects and this happened to be one of them.

AA: You had to choose a curator to work with before submitting your application for the prize. Had you worked with Mahita El Bacha Urieta before, and if not, what motivated you to choose her as your curator?

MS: When I made the application, Mahita was the first person that crossed my mind. I had never worked with her before, but we had met a couple of times and we share similar points of view about the art scene today in the sense that it is sometimes too conceptual and not always connected to the mass public. Aside from that, Mahita’s father is a painter as am I, so I felt that she would be able to relate to my works in a strong manner.

AA: So where were you when you heard that you won the prize?

MS: I was in Montreal literally in the middle of moving back to Lebanon: I was in a truck transporting my studio to the shippers. In fact, I was feeling doubtful about moving back to Beirut, also wondering whether that was the right decision for my work upon receiving a phone call informing me that I had won. So for me that was a strong sign that I was making the right decision as the project I proposed had to be made in Beirut. As they say, when you close one door another door opens!

AA: Tell me about Beirut and how it currently inspires your work.

MS: Beirut is an amazing city with a great energy and so much for the eyes to feast on, in terms of the buildings, the culture and the people. The light in Beirut is also very special, particularly in comparison to Montreal. Every place has its own specific light in terms of how it affects the colours, the mood and the objects, and I am particularly interested in catching that light in my art works. After working for a year in Beirut, only now do I think I have been able to catch it.

AA: But does being Lebanese affect the actual content and subject matter of your work? Quite a few of your works have socio-political connotations that can be traced back to Lebanon’s social and political fabric.

MS: If my works reflect that then it is unconscious. Lebanon inspires me to a certain extent, but my roots are not the only aspect that influences my work. I am perhaps more inspired by the history of art and painting for that is what really moves me. There is a chain of artists that go back fifteen thousand years, and I am fascinated with the relationship shared between the present and the past. I also read extensively and may become inspired by something that I read or even an artwork that I have seen or heard about.

AA: How would you describe the typical process of creating your work?

MS: Well there isn’t really a typical one; it is not like a recipe for a dish that you repeat over and over again. Each painting is a unique journey, deciding its own course. Some take a long time for example, some are quick and spontaneous, but I find that starting with a drawing is always helpful because drawing is unconscious and doesn’t have to be intellectualised.

AA: For an artist, the process of working is quite solitary, especially in your case since you work through the night. Do you find that the method of your art production in this respect either creates or increases your attachment to your work?

MS: Yes, absolutely. I develop a strong relationship with my work, and sometimes it is like a relationship with a woman! My works are intense and intimate and so in a way the process is a very sensual one.

AA: Speaking of sensuality, some of your works go beyond that and are even quite erotic. How does that relate to your other works, and more importantly, how does it ‘fit’ into the Middle East?

MS: As most of my works explore life and death, I perceive sexuality as related to life and death, so in that way, these works are not meant to be a provocation but actually a continuity of my explorations. As I also mentioned before, I am interested in art history, and nudity and sex have always been a part of that history. I think that in this part of the world, some people are more open to these works than others; whilst I have shown some of them in Beirut, I usually do so through private means. We should perhaps reconsider and reassess the representation of the human body in the Middle East.

AA: Finally, what does Sahmarani mean?

MS: I have no idea, but I will tell you a funny story about my name. I was in Turkey recently looking at miniatures and the salesman in the shop told me that in the past, one of the leading painters who specialised in painting the snake goddess was called Sahmarani! So I guess I have always been a painter.