Balmain (Fall 2009 Ready-to-Wear)

Style.com

John Galliano (Fall 2002 Ready-to-Wear)

Style.com

Ralph Lauren (Spring 2009 Ready-to-Wear)

Style.com

Jean Paul Gaultier (Spring 2007 Ready-to-Wear - retrospective of 1993)

Style.com

Eighteenth century: Chintz

V&A, London

Yinka Shonibare

James Cohan Gallery

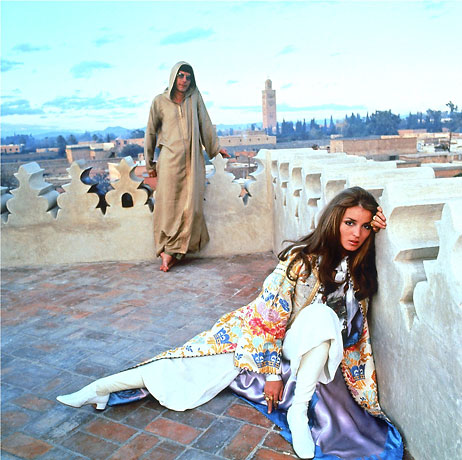

Talitha Getty

Patrick Lichfield/National Portrait Gallery

Poiret Evening Gown c. 1914

Exoticising Fashion

October 2009

Ana Finel Honigman examines Orientalism within Western fashion, and delineates its focal points of evolution and its tremendous impact upon Western fashion design.

At first glance, newly-minted American University freshman sporting bindis, kuffiyeh-s, conch shells or just a bag beaded by indigenous peoples, may seem like a different species from the ladies in Marie Antoinette's court who adorned wigs with ostrich feathers. They are joined today by tanned and dreadlocked Japanese hip-hop aficionados and bros bearing Gaucho belts who gulp down other cultures piecemeal or whole-cloth, while fashion's catwalk icons graze through vintage National Geographic magazines and seek inspiration from traditional garb in Kenya, New Deli and the rest of the globe. The Western fixation on fashion from the Middle East is at the heart of this historic trend.

Coordinating global political statements while getting dressed in the morning might seem a far cry from layering this season's Ralph Lauren Silk Charmeuse Harem Pants, priced at $1698 or £1,750 Balmain silk ‘Bollywood’ flares with bells, bangles and belts purchased in a Moroccan souk. However, it is all a byproduct of Western fashion's long-time playful plunder of ‘exotic’ looks, styles, references and influences. All across the spectrum from purely aesthetic homage to awkward and potentially offensive appropriation, the West's infatuation with the ‘exotic’ possess a complicated fluid history of creating tidal-waves of trends, many of them currently on display along the world's streets and catwalks.

This interest is not one-sided. Today, Nike sneakers, tee shirts with English slogans and Saville Row suits entering non-Western markets threaten to brush distinctive native styles aside. Yet at the same time, native traditions are admired and copied with great interest by Western designers, and often items with an ‘exotic’ provenance becoming popularized in the West and reproduced for the ‘mall’ masses. In the past, fashionable fixations on other cultures arose among the wealthy and erudite. Nevertheless, in the late twentieth-century, many of the most significant style-statements began on the street, where multi-cultural mutual curiosity generated hybrid styles mixing traditional exotic components with distinctly Western elements. Though widely worn trends can trickle down from key designers or bubble up from looser and more nebulous anonymous creative forces like streetwear, as fashion scholar Jennifer Craik explains, ‘The incorporation of exotic motifs in fashion [across all cultures] is an effective way of creating a 'frisson' (a thrill or quiver) within social conventions of etiquette.’ As a result, too much of that tension between the wearer and the items worn transforms clothes into costumes, revealing the wearer's aspirations to be misguided and merely silly affectations, therefore causing more of a shiver than a quiver.

The history of exotic trends within the West is often less of a horizontal journey than a lateral drop. Intrepid trendsetters have started styles. Travelers who are wealthy, knowledgeable, curious and courageous enough to go to remote places and witness outlandish sights brought back objects that possessed a corresponding allure. Conversely, the image of wealth and worldliness ascribed to fantastic objects or styles of dress soon attracted pretenders and poseurs and eventually became signifiers of vulgar pretension. As unusual and arresting styles became more accessible and common, their status slipped from refined to common, and from chic to chintzy.

By the seventeenth century, chintzy metamorphosed into tawdry. ‘We saw our persons of quality dress'd in Indian carpets, when a few years before their chamber-maids would have thought it too ordinary for them,’ sneered Daniel Defoe in 1708 when cheerful chintz prints transformed the garb of English ladies into gaudy gardens sprouting floral patterns. The word ‘chintz’ originated from the northern Indian word ‘chint’ meaning sprinkle or spray, though the actual technique involved patterns hand-drawn on Indian cloth with a bamboo stylus and dyed with mordants and resists, prior to being burnished with a shell or beaten with wooden mallets to develop a sheen on the surface.

The exotic also summoned up the erotic in Western imaginations. Lush and vibrant visions of Mediterranean and Middle Eastern culture served as a prime source for English romantic reverie since the seventeenth century. Pre-Raphaelite artists William Holman Hunt, Richard Dadd, Lord Leighton and John Frederick Lewis created worlds of languid harem girls, sun-soaked architecture, exotic gourmet delights and other visions for viewers in dreary, drippy England who yearned to dream of sunny far away lands and the lovers that awaited there.

Steam travel in the nineteenth-century made previously remote locales suddenly accessible, and numbers of English artists were drawn to visit and depict places like Constantinople, Cairo, Jerusalem, Morocco and Spain. Although the superficial lives of these cities were readily visible to artists, their cultures were harder to penetrate, and many of the works they produced were fragrant with mystery and myth. Sensationalist harem scenes and visions of high drama soon captivated viewers; seduced by the charm of new Orientalist imagery, Western women embraced a sartorial splendour adopted from Middle Eastern dress and decorated their homes with images of the Middle East produced by Victorian artists.

In the first decade of the twentieth-century, the great French fashion designer Paul Poiret gathered these strands together and launched a silhouette that gracefully fused Middle Eastern, Chinese and Japanese influences. The Edwardians adored sweet-pea pastilles, but Poiret presented them with a strong, rich palette inspired by nature, which he utilized for textiles, decorative schemes and sensually shaped perfume bottles. Most significantly, while other designers such as Madeleine Vionnet were softening silhouettes, Poiret revolutionized dress by dispensing with corsets and swathing women in layers of loose fabric. His models posed for promotional photographs lounging on piles of silk pillows and sporting delicate silk slippers in the style of sultry harem girls. Only a decade later, Poiret's Orientalist aesthetic was being lapped up by fashionable society. In 1910, the Ballet Russe performed Scheherazade, which inspired Poiret to craft skirts sculpted in the shape of harem pants, which he paired with tops cut with kimono-style sleeves. His pixyish and pugnacious young, provincially born wife Denise became his regular muse and a favorite subject for scandalized society rags. For Poiret's fabled ‘Thousand and Second Night’ ball, in 1911, Denise was dressed as the sultan's favorite in a golden lampshade tunic and harem pants. As the Queen of Sheba for another costume gala, she wore a gown slashed to the hip to reveal the entirety of her leg, a shocking gesture in 1914, ‘…even in the world of the Parisian haute bohème,’ exclaimed one commentary.

That look prevailed for a brief period but was overtaken by fascination with Asian and Latin American cultures until the nineteen-sixties revived an interest in Middle Eastern aesthetic references. The luxuriously slinky and opulent ‘rich hippie’ looks that dominate major international catwalks today and are beautifully exalted in Gucci advertisements and editorial spreads are the genetic descendants of the Moroccan and Native American inspired high-fashion pieces designed by Yves Saint Laurent.

The hippie spirit paid no attention to international boundaries, and its randomly assembled multi-cultural concoctions retained important aesthetic and political connotations. Sampling other cultures and subverting bourgeois disdain for difference was central to the hippie ethos. Though the hippie movement was not as multi-cultural as its interests implied, hippies were still responsible for sparking awareness of non-Western culture through all social levels. Hippies were also dedicated anti-conformists devoted to ideals of self-expression. The most significant legacy of the nineteen-sixties may be a culture's focus on ‘individuality’ that encourages its members to present themselves in distinctive, eclectic and often eccentric ways.

Although while authentic hippies preferred handmade and natural garments, the style itself was quickly commoditized and marketed. While nameless rebellious teenagers inspired Saint Laurent and his imitators to drape models in loose, flowing ‘ethnic prints’, the leading style figure who influenced fashion insiders was Talitha Getty, one of the sixties' ‘beautiful people’. The Java-born Dutch actress was the daughter of a painter and the granddaughter of the artist Augustus John. As a child, she interned with her mother in a Japanese prison camp during the Second World War, but when she grew into a slinky, long-haired beauty, she became an object of wide-spread adoration whose admirers included Conservative minister Lord Lambton and Rudolf Nureyev. In 1966, she married John Paul Getty Jr., the son of the richest man in the world, wearing a white mink trimmed mini-skirt. Talitha became best known when she befriended Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithful, who she hosted at her home in Morocco.

It was at that house in Marrakech that Patrick Lichfield photographed Paul and Talitha Getty for an image that typified ‘hippie chic’ and is regularly referenced as the epitome of ‘boho’ beauty. In the shot, Paul Getty wears a traditionally Moroccan-hooded kaftan, and Talitha slouches sensually on the floor swathed in silk and billowing harem pants. ‘It's the picture that has inspired a thousand fashion collections: Patrick Lichfield's photograph of Talitha Getty on a Marrakech rooftop with her husband, John Paul Getty, at the beginning of 1969, when the couple were the embodiment of a certain kind of 1960s glamour, a hippie-de-luxe look that has flourished ever since.’

Getty's classic Dutch features and balladic grace earned her recognition as an iconic beauty of her era and her artistic pedigree captivated couturiers, but the exotic locales she knew and frequented made her something of a pop-culture ambassador. Yves Saint Laurent cited the Lichfield image as exemplifying the era's aesthetic. He described the photograph as, ‘Talitha and Paul Getty lying on a starlit terrace in Marrakech, beautiful and damned, and a whole generation assembled as if for eternity where the curtain of the past seemed to lift before an extraordinary future.’ Alicia Drake, Saint Laurent's biographer, wrote, ‘Yves had never seen anyone like Talitha before. He took in every visual detail. He was struck by the wildness and high sexuality of it all, at that time so alien to Paris couture. It wasn't only the clothes that affected Yves; the Gettys lived with a degree of indulgence and hedonism that he had never witnessed before.’ Saint Laurent bought his own house in Marrakesh and presented kaftans and North African accessories to Paris. By 1971, when Getty died of an overdose in Rome, the exotic look she embodied was everywhere in magazines such as Vogue.

Exotic fashion today is comparatively classic. The bo-ho style pioneered and broadly popularized by pop-culture style icons Sienna Miller and Mary-Kate Olsen is mostly a lux redux of hippie chic. In 2006, teenage girls throughout the United States and the UK shopped for Moroccan leather coin belts, masses of Middle Eastern jewelry, embroidered leather slippers and flea market-inspired finds. After grazing through the major chain stores, they looked as though they had just returned from raiding a souk. The style was breezy and sexy, in the same way Poiret's fixation on the East was founded on an image of the Orient as sexually free and liberated from Western constraints.

After seasons when fashion snapped into a more sculpted reactionary set of styles, ‘haunte boheme’ returned. This time, the most arresting clashes are not simply between Caucasian wearers and non-Western styles, but between garments inspired by less prosperous countries and staggeringly high price tags. On the surface, hippie chic seems ill-fit for couture costs, but the pricing is justified by complicated craftsmanship, rare materials and careful cultural pedigrees. The prices for lux hippie looks are not radically different from other styles, but the ease and frequency with which knock-off labels mass-reproduce designer silhouettes, creating a context in which an elaborately embroidered vest might seem especially worth its high price-tag.

Just as eating hummus can offer either a superficial or a profound understanding of Middle Eastern culture and the lives of Middle Eastern people, Western appropriations of other culture's signature styles have oscillated between self-promotion through an exotic look and efforts to gain insight and enrichment from the aspirations, concerns, interests and values of the cultures being copied. However, the emergence of Middle Eastern-born and based designers including Reem Acra, Karen Karam, Mohammed Ashi and Essa on Paris's catwalks means that designers can become ambassadors of their own coveted cultural traditions.